Dom Jones - Spartathlon 2025

- Dom Jones

- Oct 10, 2025

- 18 min read

CAMINO:

Dom Jones is friend first and Camino athlete a very close second.

We've known Dom longer than there has been a Camino Inc. Dom is a local North London runner who has one of the most impressive ultramarathon CVs of any Londoner.

In 2019 Dom had a Top 10 Centurion South Downs Way 100 miler plus a UTMB finish (in barefoot shoes). He was one of the first people we knew to complete a successful Bob Graham Round and post pandemic we kept meeting Dom as he continued to get quicker and quicker.

No Doubt in our devlish ways we would have planted the Spartathlon seed back in those early days but after a scintilatting second at Autumn 100 in 2024 and an auto-qualifier our inbox buzzed and Dom came looking for the final coach guidance to start building the perfect Spartathlon debut plan.

What came next can only be described as a textbook block of dedicated training + sauna + crew prep (even a family holiday in the Sparta region!) and on towards the race itself. We've loved every second of coaching Dom for this one and continuing of decade plus love of running + coaching and supporting the event.

Over to Dom to share just how amazingly well it went - Proud of you Dom x

ckground

My Spartathlon journey starts here.

By here, I mean here on the Camino Ultra website. I read the blogs that Anna, Bryan and Miki wrote after the 2024 edition and I was hooked. The tears, the pain, the glory! While I’d been aware of the race before this, something in these stories crystalised my desire to run Spartathlon.

A week later I had a good race at the Centurion Autumn 100, closing well to finish second. On Strava, David Bone mentioned that my time was a Spartathlon autoqualifier, and with that the seed was truly planted (it has come to my attention since then that David is a prolific gardener of Spartathletes).

Training

I applied in February, and while I was technically guaranteed a place, it was still exciting and daunting to get that confirmed in March. My running had been fairly lacklustre in the first few months of 2025. I was waiting for confirmation on a date for surgery on my collarbone and this uncertainty dampened my motivation for hard training.

I had the operation in April, and gave myself a few weeks to recover. My priorities were:

Finally get to a physio and sort out long term issues I’d had with my hamstring, plus figure out a programme for strength and conditioning

Work with a coach who understood Spartathlon and could help get me in the best possible shape for it

Start adding in some passive heat training using saunas early in the build, and maintain that all the way through to September

I met David in Victoria Park in May to talk about working together. I’d already entered a couple of races, a trail 50km in June and a mountain 100km in July, but otherwise I put myself in Camino’s hands until Spartathlon. The next day a coaching Whatsapp group was set up called “Dom kisses the feet”. I thought this was an unusual approach to the athlete-coach relationship until I realised it was referring to the statue of King Leonidas in Sparta.

From May I averaged 55 miles a week for 12 weeks, climbing to just under 80 miles a week for the last 5 weeks before taper. I loved having some outside input into my training and the accountability and support that coaching provides. In general I was running my easy runs slower, spending more time at threshold, and more consistently running back to back long runs.

In those last 5 weeks the consistency I’d built started to bear fruit. A fortunately timed holiday in Greece allowed for some practice running hills in the Greek midday sun and I felt strong and comfortable in the heat. I was scheduled for a nighttime solo headtorch run while in Greece, but I chickened out after hearing the howls of the local wolves that had recently been reintroduced to that part of the Peloponnese.

While on another holiday in Cornwall, David suggested I try for both the out, and the out and back FKT on the 18 mile Camel Trail. This made for an incredibly challenging session, where I narrowly beat both the previous FKTs by ~1 minute on a warm and muggy day. Afterwards I got in the car to drive home but it took 20 minutes before my legs stopped cramping enough for me to be able to safely use the pedals.

In the weeks up to the race I mulled every piece of kit and created multiple potential options and contingencies. I’d bought so many new pairs of shoes that my wife’s eyes would roll at the sound of a knock at our door. I’d taken to hiding these boxes under my desk but I was fooling no one. I met David on Monday of race week for a last minute sauna and pep talk, the solidarity welcomed as I wrestled with the nerves of the taper.

Before the race

I finally arrived in Greece on the Thursday fit, and fresh from the reduction in training load. Among the various taper panics that included not having chosen the right shoes, extensor tendonitis, and being overly tapered, I was also concerned with catching a respiratory virus on the way to Greece. I wore a mask on the train and plane journeys to try and reduce the risk, but arriving in Athens airport I felt a scratch in my throat and a dull headache and realised that ironically I might be the infectious one. I panic bought orange juice.

I met fellow Camino’s Anna and Rich at the airport and shared a ride to our hotel. It was great to chat about Anna’s previous Spartathlon and hear her reflections on the race. Arriving at the hotel we had some dinner and met fellow British team mates including my roommate Dave Stuart (great person and font of knowledge on Spartathlon and myriad other ultras). Anna discovered that her roommates were a pair of taciturn Czech women, one of whom insisted on remaining stark naked, which prompted a rapid reallocation of rooms among the GB team.

The next day was a blur of nervous activity. I met my Dad and his partner Judith who, along with my wife Sarah, would be crewing me. I ran them through my crew plan, exchanged my drop bags for a race pack, posed for team photos, prepped my kit for the morning, and enjoyed an anxious dinner with the team before turning in for an early night.

I slept fine but despite waking in plenty of time the morning felt like a rush and I only just made it onto the bus to the start line in time, my adrenaline spiking as I realised it had almost left without me.

First 50

The start is incredibly atmospheric, with the Acropolis lit up on a hill above the plaza where runners gather. I tried to enjoy the view while waiting in the queue for the portaloos. Soon we were bunched at the start line, and after some encouraging words from my crew and with minimal ceremony, we were released onto the streets of Athens.

It was finally here. We were running through the city centre, tightly grouped - a blur of polyester. I listened to the conversations around me without taking them in, aware of the range of different languages spoken as police stopped traffic at junctions to let us pass through unimpeded. Cars honked in support and frustration. I was focused on my pace (~5:30km’s) and my heart rate (keep it under 140). I had one job in the first 50 miles - relax and don’t overcook it.

I was surprised how fast people were running past me. I’d studied historical splits and in my mind there were two approaches; go fast early and back yourself to have strong enough legs to prevent a hard fade late in the race, or start conservatively and aim to close (relatively) strong in the second half. I’d chosen the latter option, not wanting to take the risk of blowing up and ruining my first Spartathlon, and comforted by the fact that plenty of British runners had run sub-30 (and even sub-27) pacing the first 50 miles around 8 hours.

As we moved onto the hard shoulder of the main road out of Athens, I tried to settle into an easy rhythm, adjusting for the slight ups and downs as they came. It’s not a particularly charming part of the course, and for much of it you are running close to traffic but there were plenty of people on the roads encouraging us as we went past. I tried to stay relaxed, telling myself the first 50 miles was just the warm up to get to the real start line at Corinth.

About 10 miles in I noticed that the bracelet my daughter Leonie had made me is missing from my left wrist, and instead there’s a large scratch down my arm. I think about her, decorating it with alternating watermelon and pizza slices, to remind me to keep eating and having fun. I’m briefly sad, but reframe it as a gift to the trail gods, hoping that they’ll look favourably on me today. I’m aware this race will likely take everything that I have to give and more, but I don’t need the bracelet to remind me how loved and supported I am. I think about all those here in Greece and at home who are wishing me well.

A marathon in and I see my crew for the first time at CP12 in Megara. They’re amazing; they give me drinks, gels, sunscreen, a full ice bandana. Every crew point from here they get more efficient, more dialled. I’ve been drinking electrolyte drink and eating gels in a steady rhythm. Running out the crew point I see another runner vomiting heavily in the road. I give him a sympathetic look, but I feel amazing as I glide up the gentle hill, ice water dripping down my neck.

We’re on a stretch of coast now and it’s glorious running. It’s beautiful. It’s why I’m here. The sea is on the left, hills on the right, and the road snakes through the countryside past beaches, oyster sellers, restaurants, through villages. It’s properly hot now, and every chance I get I hold ice in my hands, sponge water on my head and shoulders, and refill my bandana.

I’ve passed a few GB runners along the way and now I’m running and chatting with Peter Abraham. We pass a checkpoint and I ask him if it’s CP15, where I have a drop bag. It is and I’ve missed it. I consider running the 60 seconds back to it, but no part of me wants to run back towards Athens. Peter kindly offers me supplies but I’m not too concerned. At the next aid station I quickly scan what’s on offer and select a 100g pouch of pure honey to replace my gel and some crisps and coke to replace my electrolyte drink.

I keep moving, sucking the thick honey from its pouch. I’m a running machine, turning this humble food into fuel for my body. I’m Pheidippedes, running through Greece eating only what he can forage! A few miles later I experience shooting pain in my liver which reduces me to walking for a few steps. I curse the honey, curse my choices. I should have gone back for the drop bag. At the next aid station I find Tailwind and some gels and I’m back in business.

It’s hard going at times, running up hills and into strong headwinds on the side of a busy A road. The heat is constant, and I’m no longer able to convince myself that this first 50 miles is ‘just a warm up’. I'm starting to feel beaten up but at CP19 I’m able to pick up my next drop bag. I eat a gel and perk up. Soon I’m crossing the iconic Corinth bridge and meeting my crew again. I change my socks, check that my feet are ok. Reapply lube, eat some watermelon. Drink some fluids: coke, water. Pick up some gels.

Second 50

50 miles done and I’m back on the road. I reflect on the first 50 miles and give myself a pat on the back for coming in right on my target pace of just under 8 hours, not falling into the trap of pushing too hard, and staying on top of my fuelling. That said I feel like I’ve spent the first section slightly obsessively monitoring my heart rate and pace, and so I commit to running the next section by feel and enjoying it more. From here I’ll also get to see my crew every 10km or so, which is a huge boost.

The road winds through olive groves and I settle into a comfortable rhythm. I’m running with more flow now and steadily passing people. I chat with a German man who starts to throw up but doesn’t let that stop him running even for a moment. I push on ahead but after a few minutes still hear him running uncomfortably closely behind me. I turn around and realise it's the ice moving in my bandana which sounds like feet on tarmac. I’m completely alone.

It’s still baking hot and I keep passing people, leapfrogging with others as we run through small villages, receiving high fives from kids and cheers from those who’ve come out to watch the runners. I fill up with water at the checkpoints until I see my crew again amongst the beautiful ruins of Ancient Corinth. I feel amazing as I run through the old town, all fresco diners cheering us as we pass their restaurants. I chat with my crew as they help me replenish my supplies, my eyes swiveling wildly as I try and take in 3000 years of history while rubbing more lube onto my inner thighs.

I keep moving. I reflect on what I’m doing and why. A Greek messenger was once sent from Athens with a message to Sparta requesting help. The fate of all Athenians, some would argue Western civilisation itself, rested on him accomplishing his mission. I try and channel this energy as I run through the Greek countryside. I am on a mission. I have to get to Sparta and deliver a message. Nothing will stop me.

My crew have been given instructions to feed me solid food so at the next aid station I eat some banana and watermelon to keep them happy and I keep moving. The fruit is sitting very badly in my gut but I now seem to be running entirely through roads lined with supporters and there’s nowhere private I can dash to. The fate of Western civilisation rests on me not soiling myself. I keep on moving.

We get into some long and grindy sections of road and what feel like the first proper hills, and I start yoyoing with Matthew Ma. It’s nice to see a friendly face and he’s running well. It’s getting cooler and my constant need to urinate suggests I need to reduce the amount I’m drinking. My crew are trying to manage me, getting more solid food in, but after the last hour of GI distress it’s not what I want. I want plain water, and gels. At CP 32 in Halkeion I begrudgingly drink some chicken soup and it’s perfect, an antidote to all the sugar. I add it to my rider.

It’s dusk and I don my reflective vest and head torch. I reach CP35 at Ancient Nemea, it’s half way and it's starting to get dark. My legs still feel good, and now that I’ve found a better formula for my nutrition my energy picks up. I remember something Camille Herron said about her 2023 Spartathlon, where she described ‘going feral’ at this point of the race, becoming in her words ‘hyper focused’ in order to chase down her competitors. I try this mindset on and like it. Readying myself for the climb to the mountain, I take a decent amount of caffeine and some vitamins. I eat a lot of rice pudding. I down soup and coffee. I’m ready to run into the night and start chasing people down.

In my race plan the second 50 miles is about pressing to maintain the momentum when everyone else will be fading. I tell myself that everyone is hurting but that I will deal with this discomfort better. There’s a climb and another descent before I see my crew again at Malendrini. More caffeine. Another descent and now I’m at the base of the main climb up to Mount Parthenion and I’m moving well, focused, enjoying using different muscles. I click into a higher level of effort, careful to keep it manageable, just focused on the small pool of light cast by my headtorch and the chain of lights above that follow the road winding up the mountain.

I’m passing runners steadily now and as I arrive at Lyrkia where my wife is waiting I’m locked in and in a hurry. I want gels. I want caffeine. I need to go. I see a look of slight concern in her eyes but I’m gone back into the night and back to the grind of the hill. I tell myself I’ll run every step. My legs hurt but I’m not generating enough power to worry about lactate, so I just keep pushing, thinking about my training, the hours running hills, the hours on the treadmill, the weight sessions.

I’m in the zone now winding up to the mountain base, where I meet Sarah again. I’m overwhelmed with gratitude for my crew. My dad is almost 80 and he and his partner Judith have been driving all day and most of the night to support me. My wife flew in after work on Friday and has to fly home on Sunday evening but has high confidence in my plan to finish before 3pm when she needs to leave for the airport. My mum’s at home with our children. I can’t imagine doing this without them.

I drink soup, take water and gels, drink coffee. I change into a new vest and light windbreaker for the mountain and leave the checkpoint with purpose, passing more people on the way out. I’m striding up the steep path and stairs, and it reminds me of Anna saying the mountain is like the climb up Box Hill where we’ve both been training. I keep pushing and pass more people. It’s fine. It’s nice to be hiking. It doesn’t feel long until I’m passing the checkpoint tent that marks the top. I resist the urge to stop and roll straight past nursing my legs carefully on the steep and sketchy trail back down.

Final 50

Finally I’m back on the road, back in a rhythm and enjoying the cool and the dark. My legs feel strong and at the Nestani aid station I’m wilder still. I care only about picking up my caffeinated gels and I want to get going immediately. My wife has to rein me in; she reminds me I need the bathroom, need a spare headtorch battery, stops me almost leaving without my water. I concede, but I hate to stop, I’ve got momentum and I need to leave the aid station and keep running people down like Pacman. A few minutes later and I‘m back on the road. I mutter ‘wacka wacka’ under my breath as I pass another runner.

It starts to rain gently. At Zeygolatio I see my dad and swap my vest for a dry t-shirt. He tells me that he’s just seen another GB runner, Tim, who is struggling with a knee and ankle injury. A little while later I pass Tim, who is moving well but clearly in a lot of pain. I think what a cruel sport this is, one misstep can be the difference between triumph and disaster. Now the rain picks up and my dry t-shirt is soaked. I realise that my wife is asleep in the car with all my spare running kit and waterproof jacket. I’m already on the edge of being too cold, I’m wet, and the temperature is still dropping. This could be my disaster.

I stop under a bus shelter and consider my options. I remember I have arm sleeves in my pocket. I’ve lost one, but one is better than none. I keep running. The rain is getting worse. At the next checkpoint I ask for a bin bag. I punch a hole through the bottom and as I push my head through this hole I claw two holes in the side for my arms. I put my reflective lights back over this makeshift binbag gilet and keep running. A few minutes later and I’m the perfect temperature. I’m ultra Ray Mears. Nothing will stop me getting this done.

At some point I’m on the second mountain, or at least I’m running on a steady uphill gradient on the hard shoulder of another A road. It’s endless but that’s fine. I'm going to bury myself running up this hill in my binbag in the dark and rain. This is what I came for, although this is not how I imagined it, my feet soaking in cold puddles, catching road spray in the face from passing trucks.

I tick off the aid stations one by one and tell myself to run the mile I’m in. At CP65 my crew are back together, having taken a few hours of sleep in shifts. It’s like a mobile field hospital, with runners in space blankets huddled together in the dark drinking soup. My dad tells me that it’s all downhill from here and I curse him quietly 10 minutes later as I continue to climb another endless drag of a hill. It's really the only misstep in an otherwise flawless crewing performance.

I'm filled with gratitude that I get to share this experience with him and my wife. I know they would still be proud if my race ended early but I'm doubly appreciative that it's turning out to be a day to remember. Even the most conservative calculations have me arriving in Sparta now in a good time, bar anything drastic happening.

At some point I realise that all the mental calculations I’ve been doing are based on the distance of the Spartathlon being 253km, but in fact it is 243km. I have gained 10km in an instant! I am filled with joy as I knock an hour off my rough finish time. I realise I should have paid more attention to the map, the stats, the course as I find myself running what seems to be an unexpected third mountain but it doesn’t matter now. I grant myself 10 seconds walking, then 20, then 30.

The relaxation I felt in the first 50 miles has gone. The aggression I felt in the last 50 miles has gone. Now there’s just effort and pain. For a while I resort to the breathing exercises my wife was given to use during childbirth, exhaling hard through pursed lips. It’s helping. I make a mental note to never publically compare my experience running Spartathlon to my wife’s experiences of labour.

The km markers at the aid stations are my Bible and I tick off each 0.1km between them religiously as they appear on my watch. I’m still eating gels and drinking water. The sun is up but it's cool and overcast as I finally see a glimpse of what I assume is Sparta way off in the distance at the foot of this hill I’m running down. I’d hoped this downhill section would come as a relief given the 650m+ elevation loss, but somehow it still feels mostly flat or uphill on my tired legs. The vision I’d had of me running this section hard is laughable, a distant memory.

I see my crew for a final time and they’re elated. Every step from here is an effort but I'm still running and before too long I’m at the final aid station on the entrance to Sparta, where I ditch my bottle and cap and pick up a fresh GB top and Union Jack. A police car pulls in behind me and shadows me as I slowly make my way through the quiet streets of Sparta. I wave up to the balconies from where the sporadic cheers of Greek grandmothers spur me on. I let myself feel a moment of pride, for being here, for doing this.

I turn right and finally I see Sarah with my dad and Judith and press on to meet them, scanning for the statue which is straight ahead but still hidden from view. I wave my flag, picking up pace. I can’t believe I’m here, and that it is over. I ascend the steps. I kiss the feet.

I turn and hug Sarah, and I’m overwhelmed with gratitude and love for the support they’ve given me to achieve this goal. So much of my energy and attention has been directed towards this one aim for the last 4 months, it’s surreal to finally be here.

After the race

I drink water from the River Evrotas and I’m crowned with a wreath of laurel (or olive?). I'm asked to say some words into a microphone, but it’s 9am and raining in Sparta so there’s no one here to hear them. I earnestly praise the race, the people of Greece, the country itself for having given me this experience.

Two women appear under my shoulders and manhandle me into the medical tent. I want to walk about a bit and soak in the experience but they don’t permit discussion. I drink chocolate milk while they assess the damage, I’m fine, aside from a few blisters on my toes. Someone helps me to the toilet, regarding my attempts to walk there unaided with skepticism. I’m offered what turns out to be a very gentle, almost sensual massage that serves no purpose but to make me oily and uncomfortable.

For a second I consider waiting in town to see other runners arrive, but tell myself I’ll enjoy it more once I’ve been back to the hotel and changed. Once in the car I recount my experience of the race to my wife. It’s partly for my own benefit to unpack what on earth has just happened.

Back at the hotel I consider going down for lunch but on getting up from my bed I almost immediately feel faint and have to lie down. When I wake up my wife has left for the airport and I lie in bed catching up on messages and the news from the rest of the team and crew. My time of 26:15 placed me 14th overall, and put me on the all time top 10 list of British runners at Spartathlon, in one of the fastest GB debuts ever. I can’t really process that information, it’s beyond anything I imagined.

I’m over the moon. I don’t get back to Sparta in the end but catching up with my British team mates over dinner it’s clear just how lucky I am, as I learn about the various ways that other people’s races have played out.

Over the next few days we share our Spartathlon stories and our plans for the future. Being here with the British team has made this a really special experience, and I’ve loved getting to know this amazing group of people all bonded by our shared ambition.

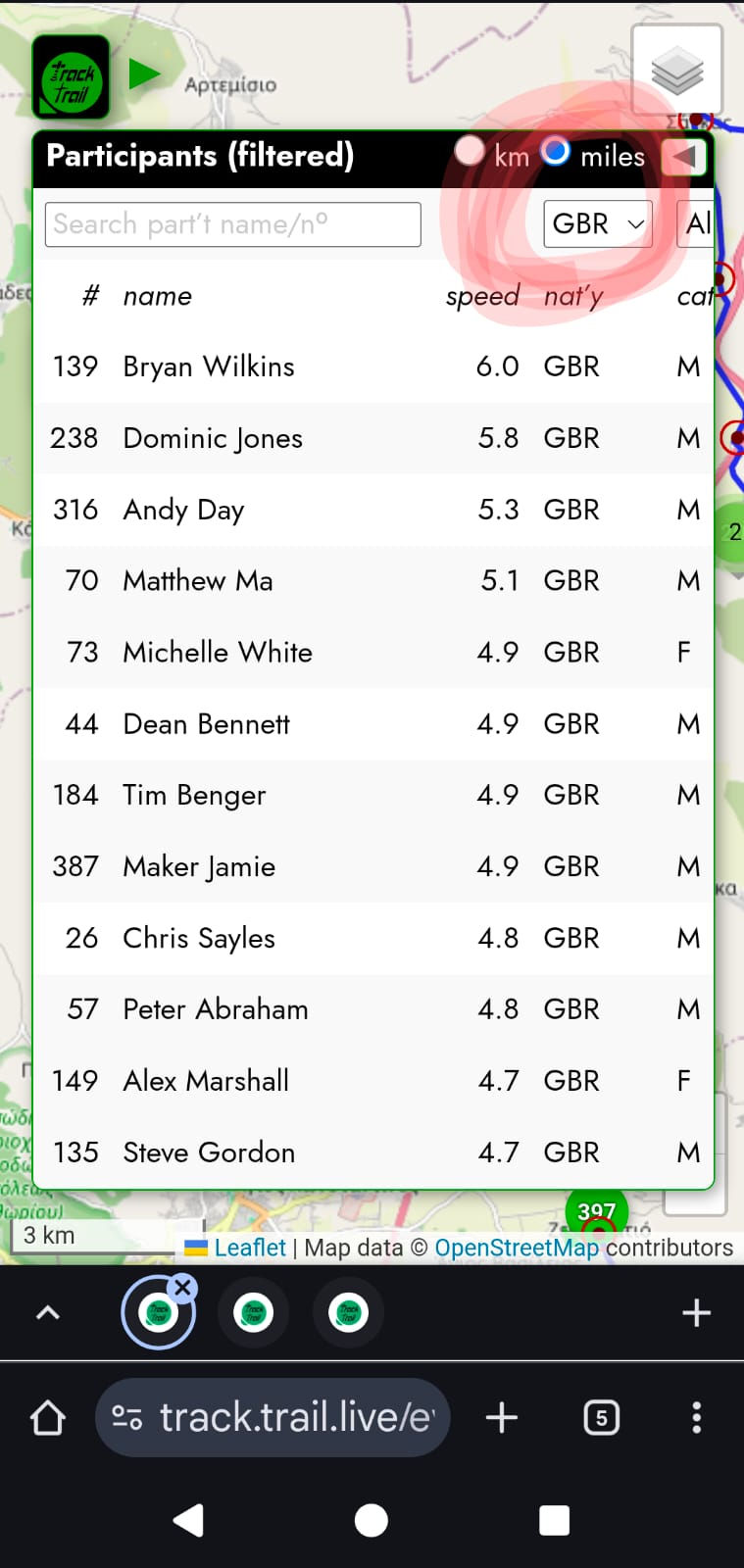

Congratulations to all those who finished, especially Bryan Wilkins who won the Michael Graham Callaghan Trophy for Best British Male Performance for the 2nd year in a row (Bryan placing in the overall top 10 with a stunning time of 25:26), and Chelle White who won the Lizzie Hawker Trophy for Best British Female Performance (finishing 5th Brit in 31:34). Huge congratulations as well to Ian Thomas who finished the race for a truly inspiring 10th time in 34:24 to gain a lifetime autoqualifier. Commiserations to all those on the team who didn’t have the day they wanted - I hope it fuels whatever adventure you choose next. Finally thanks to all the sponsors of the British Spartathlon team.

Reflecting on my race, I’m 100% content with my first Spartathlon. Would I come back? My immediate answer is not for a while, but looking around at the number of repeat Spartathletes I can see that that might change. I know a fair few of the GB team will be back again in 2026, and it’ll be hard watching their epic journeys from afar now I’ve experienced the magic of the race. I’ve done the maths already and made a mental note that my Spartathlon finish time counts as another AQ for Spartathlon just in case I change my mind.

Comments